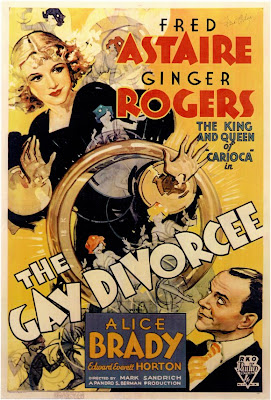

After reviewing “Flying Down to Rio†last fall, I decided to re-watch all of the Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers movies in sequence and blog about them during the next year.I love their movies â€" the magnificent musical numbers in both song and dance (which, if you think about it, probably comprises about one tenth of each film), their sense of style and fun, and the fact that no duo has ever been this consistently good since. So, this isn’t really a chore; I’m indulging myself, and you get to watch (or roll your eyes!).My favorite reference book on these films is “The Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers Book†by Arlene Croce. She breaks down each film by plot and dance.It’s worth noting that “The Gay Divorc! ee†was a first on many levels: the first starring movie for Astaire and Rogers as a duo (“Rio†had them as supporting players); the first to feature regular supporting players, such as the excellent Edward Everett Horton, Erik Rhodes and Eric Blore; the first to bring together producer Pan Berman, choreographer Hermes Pan (unbilled in this film) and director Mark Sandrich, who would direct five of their 10 movies; the first to feature a form of the mistaken identity/mix-up plotline that would be come routine in their films; and the first to feature full-length solos by Astaire (he had a brief one in “Rioâ€).It also continues a few patterns from “Rio,†including the stylized Art Deco sets that became known as the “black and white†sets, and the big production number to a specific dance craze (in Rio, it was the Carioca; here it’s The Continental).“The Gay Divorcee†opens in a Paris club with chorus girls using finger-puppet dancers. The movie then pan! s to Guy Holden (Astaire) and Egbert Fitzgerald (Horton), both! with si milar finger puppets. Guy, a famed dancer, figures out how to use his quickly, while Egbert, a pampered lawyer, is a bit clueless, which pretty much tells you what you need to know about these characters. When the two men can’t pay their bill, Fred must dance a solo to prove who he is. It’s a quick dance but one that shows off his skills, and it is Astaire’s first solo as a leading man.When Guy and Egbert return to England, they run into Hortense (Alice Brady) and her niece, Mimi (Rogers). However, they don’t run into them together. Guy ends up causing an incident with Mimi’s dress; Hortense recognizes Egbert as an old beau.Hortense ends up hiring Egbert, a lawyer, to handle Mimi’s divorce case. The plan is to whisk her away to a seaside resort, where Egbert will hire a man to spend the night in Mimi’s room. The next morning, they will be “discovered,†and the divorce can be put in motion.Meanwhile, Guy can’t get Mimi out of his mind, unaware that Egbertâ! €™s case involves her.The movie is based upon a stage musical starring Astaire, although much of the music was removed and the plot was rewritten for the film. Cole Porter’s “Night and Day†had been a big hit for Astaire, which certainly helped this film.RKO was taking a big chance with “The Gay Divorcee.†Astaire and Rogers were not proven box office stars, and that’s why you find some fluff in this movie, particularly the size of the supporting roles. RKO wanted to make sure the audience would be entertained in case the Astaire/Rogers pairing didn’t work.

After reviewing “Flying Down to Rio†last fall, I decided to re-watch all of the Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers movies in sequence and blog about them during the next year.I love their movies â€" the magnificent musical numbers in both song and dance (which, if you think about it, probably comprises about one tenth of each film), their sense of style and fun, and the fact that no duo has ever been this consistently good since. So, this isn’t really a chore; I’m indulging myself, and you get to watch (or roll your eyes!).My favorite reference book on these films is “The Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers Book†by Arlene Croce. She breaks down each film by plot and dance.It’s worth noting that “The Gay Divorc! ee†was a first on many levels: the first starring movie for Astaire and Rogers as a duo (“Rio†had them as supporting players); the first to feature regular supporting players, such as the excellent Edward Everett Horton, Erik Rhodes and Eric Blore; the first to bring together producer Pan Berman, choreographer Hermes Pan (unbilled in this film) and director Mark Sandrich, who would direct five of their 10 movies; the first to feature a form of the mistaken identity/mix-up plotline that would be come routine in their films; and the first to feature full-length solos by Astaire (he had a brief one in “Rioâ€).It also continues a few patterns from “Rio,†including the stylized Art Deco sets that became known as the “black and white†sets, and the big production number to a specific dance craze (in Rio, it was the Carioca; here it’s The Continental).“The Gay Divorcee†opens in a Paris club with chorus girls using finger-puppet dancers. The movie then pan! s to Guy Holden (Astaire) and Egbert Fitzgerald (Horton), both! with si milar finger puppets. Guy, a famed dancer, figures out how to use his quickly, while Egbert, a pampered lawyer, is a bit clueless, which pretty much tells you what you need to know about these characters. When the two men can’t pay their bill, Fred must dance a solo to prove who he is. It’s a quick dance but one that shows off his skills, and it is Astaire’s first solo as a leading man.When Guy and Egbert return to England, they run into Hortense (Alice Brady) and her niece, Mimi (Rogers). However, they don’t run into them together. Guy ends up causing an incident with Mimi’s dress; Hortense recognizes Egbert as an old beau.Hortense ends up hiring Egbert, a lawyer, to handle Mimi’s divorce case. The plan is to whisk her away to a seaside resort, where Egbert will hire a man to spend the night in Mimi’s room. The next morning, they will be “discovered,†and the divorce can be put in motion.Meanwhile, Guy can’t get Mimi out of his mind, unaware that Egbertâ! €™s case involves her.The movie is based upon a stage musical starring Astaire, although much of the music was removed and the plot was rewritten for the film. Cole Porter’s “Night and Day†had been a big hit for Astaire, which certainly helped this film.RKO was taking a big chance with “The Gay Divorcee.†Astaire and Rogers were not proven box office stars, and that’s why you find some fluff in this movie, particularly the size of the supporting roles. RKO wanted to make sure the audience would be entertained in case the Astaire/Rogers pairing didn’t work.  But it did. As Croce astutely wrote in her book, “When one considers that only ten minutes out of the total running time of ‘The Gay Divorcee’ are tak! en up by the dancing of Astaire alone or with Rogers, the film! ’s end uring popularity seems more than ever a tribute to the power of what those minutes contain.â€You can see it in the first full number. Outside of the short dance Astaire does in the Paris nightclub, the next number is a magnetic solo, “A Needle in a Haystack.†Here Guy is preparing to find Mimi and dances as he gets ready. He’s up on a chair or catching his hat and umbrella from his valet, and the number ends with him heading out the door. It moves the plot along while being exuberant, creative and full of life. Astaire was probably unlike anyone on film before, and he carries this standard through nearly every solo he put on film throughout his career.Also, think of this: This number was without a partner, chorus girls, a chorus line or anything else that you might expect from a dance sequence. For an untried movie star, this was revelatory.

But it did. As Croce astutely wrote in her book, “When one considers that only ten minutes out of the total running time of ‘The Gay Divorcee’ are tak! en up by the dancing of Astaire alone or with Rogers, the film! ’s end uring popularity seems more than ever a tribute to the power of what those minutes contain.â€You can see it in the first full number. Outside of the short dance Astaire does in the Paris nightclub, the next number is a magnetic solo, “A Needle in a Haystack.†Here Guy is preparing to find Mimi and dances as he gets ready. He’s up on a chair or catching his hat and umbrella from his valet, and the number ends with him heading out the door. It moves the plot along while being exuberant, creative and full of life. Astaire was probably unlike anyone on film before, and he carries this standard through nearly every solo he put on film throughout his career.Also, think of this: This number was without a partner, chorus girls, a chorus line or anything else that you might expect from a dance sequence. For an untried movie star, this was revelatory. Finally, an hour into the film, we get the first Astaire/Rogers number, “Night and Day†(above). He’s in white tie and tails; she’s in a gorgeous simple dress. As the dance builds dramatically, the tension between slowly gives way as he seduces her, finally lowering her onto a seat and offering her a cigarette. There was no need for kissing or sex. Their chemistry is immediate, their dancing done as one.Two things would improve after this dance. First, some of Rogers’ arm and shoulder moves aren’t nearly as elegant as they would become, and her gait lacks a certain graceful quality. That would change very soon. Second, the sequence has numerous edits and remote camera angles (one shot from under a table, another through window blinds). This too would change soon, as Astaire would insist upon full-body shots and as few edits as possible.Th! ese are minor complaints to a breathtaking number. It’s the ! number w here Astaire and Rogers really click, and it’s solidified not long after with “The Continental†(below), which goes on for nearly 20 minutes. At the beginning of the number, the two look completely at ease with each other as they sing the beginning of the song on a hotel balcony. Then they race down to the dance floor and provide a dance full of joy and fun, even if it isn’t particularly intricate.

Finally, an hour into the film, we get the first Astaire/Rogers number, “Night and Day†(above). He’s in white tie and tails; she’s in a gorgeous simple dress. As the dance builds dramatically, the tension between slowly gives way as he seduces her, finally lowering her onto a seat and offering her a cigarette. There was no need for kissing or sex. Their chemistry is immediate, their dancing done as one.Two things would improve after this dance. First, some of Rogers’ arm and shoulder moves aren’t nearly as elegant as they would become, and her gait lacks a certain graceful quality. That would change very soon. Second, the sequence has numerous edits and remote camera angles (one shot from under a table, another through window blinds). This too would change soon, as Astaire would insist upon full-body shots and as few edits as possible.Th! ese are minor complaints to a breathtaking number. It’s the ! number w here Astaire and Rogers really click, and it’s solidified not long after with “The Continental†(below), which goes on for nearly 20 minutes. At the beginning of the number, the two look completely at ease with each other as they sing the beginning of the song on a hotel balcony. Then they race down to the dance floor and provide a dance full of joy and fun, even if it isn’t particularly intricate. The song won an Oscar that year, the first time the Best Song category was contested (it bested “The Carioca†from “Flying Down to Rioâ€). “The Continental†continues with rows of dancers, moving with precision, changing costumes from all black to all white to a mixture of both. You have revolving doors with girl! s clad in either black or white twirling inside them. This number may not have the geometric intricacies of a Busby Berkeley number, but it’s far more interesting than the drawn-out “Carioca†number from “Rio.â€Speaking of Berkeley, the first thing that surprised me about seeing “The Gay Divorcee†again is its nod to the famed choreographer and director, one of the innovators of movie musical the year before. The opening number with its rotating platform of pretty women and the finger puppets seems like something from Berkeley, as does Guy’s search for Mimi, in which pictures of pretty women are superimposed over his image of stopping one woman after another in hopes it’s Mimi. A later number, “Let’s K-nock K-neez,†has some geometric choreography (minus the overhead shots) that Berkeley was famous for.As for that number, it’s played out between Horton and a young teenage ingenue who would become a big box office attraction during World War II â€" B! etty Grable (below with Horton). The number is a bizarre bit, ! but Hort on is so much fun in a role that had to be written as intentionally fussy (I mean, he was nicknamed “Pinky†as a child because he was always toddling around home in pale pink pajamas â€" what a hoot!). Horton is a great sidekick for Astaire â€" popular enough to return in two later Astaire/Rogers films.

The song won an Oscar that year, the first time the Best Song category was contested (it bested “The Carioca†from “Flying Down to Rioâ€). “The Continental†continues with rows of dancers, moving with precision, changing costumes from all black to all white to a mixture of both. You have revolving doors with girl! s clad in either black or white twirling inside them. This number may not have the geometric intricacies of a Busby Berkeley number, but it’s far more interesting than the drawn-out “Carioca†number from “Rio.â€Speaking of Berkeley, the first thing that surprised me about seeing “The Gay Divorcee†again is its nod to the famed choreographer and director, one of the innovators of movie musical the year before. The opening number with its rotating platform of pretty women and the finger puppets seems like something from Berkeley, as does Guy’s search for Mimi, in which pictures of pretty women are superimposed over his image of stopping one woman after another in hopes it’s Mimi. A later number, “Let’s K-nock K-neez,†has some geometric choreography (minus the overhead shots) that Berkeley was famous for.As for that number, it’s played out between Horton and a young teenage ingenue who would become a big box office attraction during World War II â€" B! etty Grable (below with Horton). The number is a bizarre bit, ! but Hort on is so much fun in a role that had to be written as intentionally fussy (I mean, he was nicknamed “Pinky†as a child because he was always toddling around home in pale pink pajamas â€" what a hoot!). Horton is a great sidekick for Astaire â€" popular enough to return in two later Astaire/Rogers films. Eric Blore, playing a waiter, was already in his second Astaire/Rogers film and would appear in three more. Erik Rhodes was making his first ever film appearance as Tonetti and is hilarious as the married family man who takes his job as a for-hire gigolo to help break up marriages. His slogan: “Your wife is safe with Tonetti â€" he prefers spaghetti.â€Brady can be a handful to watch, but she does give it her all as the ! flighty Hortense and her timing is expert with such comedic lines with expertise: “There’s nothing different about (men) but their neckties.†After a solid career in silents, she had returned to the stage, only to come back to Hollywood in the 1930s and establish herself as a dependable supporting player. This was her only appearance in an Astaire/Rogers film.But RKO needn’t have worried about padding the film. Astaire and Rogers were a success as a team and marvelous to watch together. They were defining a new style for movie musicals, even if they didn’t realize it at the time. If Astaire was worried about becoming part of another established duo â€" his stage career had been formed with his sister Adele â€" he and Rogers were friendly and respectful of each other.“The Gay Divorcee†may be a little creaky in the story department and heavy on the supporting players, but when the stars are together, it’s glorious. Audiences must have thought so, because the ! film was a success â€" and so were Astaire and Rogers. They we! re on th eir way.

Eric Blore, playing a waiter, was already in his second Astaire/Rogers film and would appear in three more. Erik Rhodes was making his first ever film appearance as Tonetti and is hilarious as the married family man who takes his job as a for-hire gigolo to help break up marriages. His slogan: “Your wife is safe with Tonetti â€" he prefers spaghetti.â€Brady can be a handful to watch, but she does give it her all as the ! flighty Hortense and her timing is expert with such comedic lines with expertise: “There’s nothing different about (men) but their neckties.†After a solid career in silents, she had returned to the stage, only to come back to Hollywood in the 1930s and establish herself as a dependable supporting player. This was her only appearance in an Astaire/Rogers film.But RKO needn’t have worried about padding the film. Astaire and Rogers were a success as a team and marvelous to watch together. They were defining a new style for movie musicals, even if they didn’t realize it at the time. If Astaire was worried about becoming part of another established duo â€" his stage career had been formed with his sister Adele â€" he and Rogers were friendly and respectful of each other.“The Gay Divorcee†may be a little creaky in the story department and heavy on the supporting players, but when the stars are together, it’s glorious. Audiences must have thought so, because the ! film was a success â€" and so were Astaire and Rogers. They we! re on th eir way.Great classic films, best all time movies

No comments:

Post a Comment